Themes of Loss and Triumph: Beethoven’s Incessant Hum

A Preview by Betsy Schwarm

Spoiler alert: Beethoven was deaf! Of course, anyone reading this article already knew that, and likely also knew that 2020 will bring the 250th anniversary of the master composer’s birth. However, it is both facts, not just the latter, that inspired an upcoming multi-disciplinary performance of a newly commissioned play by Colorado playwright Jeffrey Neuman.

Barbara Hamilton, Jeff Neuman, and Mare Trevathan all came together to build the concept. Like any performing classical musician, Hamilton was already well familiar with the historical record of Beethoven’s challenges and how he coped with his disability. For the others, it was a learning process. Trevathan observed, “I was pretty baffled by how someone without hearing could COMPOSE music [that is, not just play it].… However, Beethoven describes his method of composing and while it’s the workings of genius, it’s also a concrete and comprehensible process.” In brief, he understood the process of composition well enough to be able to write down notes that would capture the unheard sounds in his imagination.

Neuman calls it “a play about loss – what loss is and how we deal with, accept, and overcome it.” The initial idea came not from Neuman, but from Barbara Hamilton, Violist and Executive Director with the Colorado Chamber Players. With the Beethoven anniversary approaching, Hamilton began considering how the Chamber Players could acknowledge the occasion with something more than a straight-forward program of quartets, trios, sonatas, and the like. Hamilton says that from the very beginning, she imagined “a theater-music hybrid.” Once actor/director Mare Trevathan introduced her to Neuman, the match was made. As a playwright, Neuman was a perfect choice for a stage work with music devoted to Beethoven: he is himself profoundly hard of hearing, and, like Beethoven, that condition came upon him in adulthood. Hamilton attests, “We wanted someone who understood Beethoven’s emotional world, to write the script.” The title, Incessant Hum, was suggested by Hamilton, who wanted to evoke the tinnitus that afflicted the composer in his later years.

Surely, one must suppose, Beethoven must have experienced both pain and fury in looking at notes on the page, knowing that it would be left to others to experience them, but how did the man himself actually feel? Fortunately, Beethoven was a prolific letter writer many of whose correspondents, apparently sensing his historical importance, troubled themselves to save and eventually publish his letters. So we know what he felt: first denial, then frustration, then anger and despair. Last of all came, if not exactly a sense of triumph, then at least a sense that “I can still do this – and I must.”

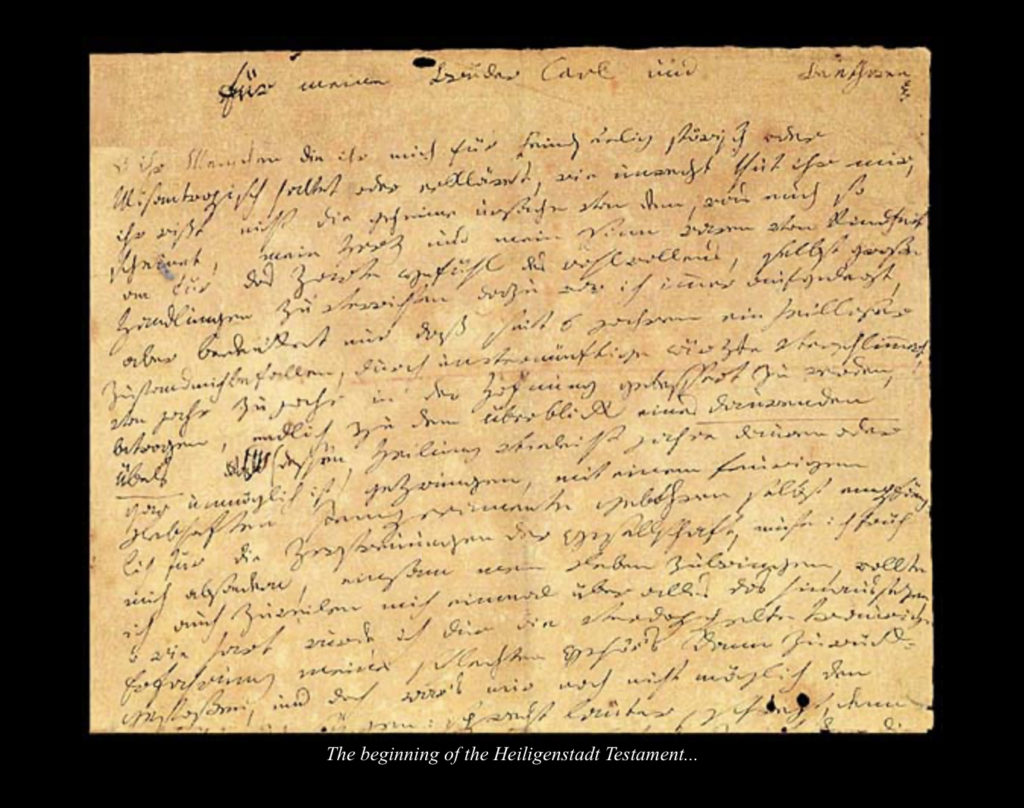

Playwright Neuman says it was in the letters that he found the soul of the work: “I became fascinated with those letters and they became, in many ways, the cornerstone of this play. They, the letters, are filled with an ache, despair, and fear that is singular to a person who is losing the thing they value most, a thing that they feel defines who and what they are.” One particularly famous letting, the so-called Heiligenstadt Testament, written by the composer in 1802 to his two brothers in an attempt to clarify his situation, became what Neuman calls “the narrative springboard for the entire play.”

The Heiligenstadt, says Neuman, “is used verbatim in several parts of the script,” including the following excerpt: “Ah, it seemed to me impossible to leave the world until I had brought forth all that I felt was within me.” Director Trevathan adds: “The hellish grief is still there. Beethoven’s letters are full of sorrow and longing and rage. But from his desperation rises tenacity. He doesn’t succumb entirely to his depression, though he contemplates it. But somehow he composes Ode to Joy.”

Neuman’s script involves two actors, one male and one female, “their narrative arch in conversation with live music.” The male voice is Beethoven; the female Neuman has named Elise: yes, as in the piano piece Für Elise. The playwright admits that she is no specific acquaintance of the composer, but rather that she is “a nebulous figure. Is she Fate? Is she a guardian angel? Is she a physical manifestation of his innermost voice? Beethoven had many shadowy women in his life, so this play is a tip of the hat to those women… it was written in a highly theatrical epistolary style.”

For this “theater-music hybrid,” Hamilton selected portions of Beethoven’s chamber music, for strings and piano in various combinations. As she explains, “Some of the music was chosen to fit the chronology of Beethoven’s gradual hearing loss. For example, the Pastorale Symphony excerpt directly reflects Beethoven’s walk with his friend Ferdinand Ries, and Beethoven’s inability to hear a shepherd’s pipes on the walk, and subsequent frustration. [That tale is related in the Heiligenstadt Testament]. Other music portrays the mix of emotion Beethoven experienced.” So the String Quartet, op. 95, “expresses defiance against fate,” whereas the String Quartet, op. 132 “delves into the loss he felt, but being able to rise above the loss.”

Some stage plays use music in an incidental fashion, leaving it thoroughly subservient to the words and the stage action. Not here. As Trevathan, who directs Incessant Hum, observes, “The music isn’t ornamental to the show; it’s essential. The music creates emotional transition for both the actors and audience. It’s as if we hear the inner monologue of Beethoven as the musicians play.” Later productions may choose different musical selections; one North Carolina production is already in the planning. However, one cannot help but suppose that the music included in the Denver area premiere performances may be the best options, as Neuman himself began hearing them early in the creative process.

Perhaps with Incessant Hum, and with the Beethoven anniversary as a whole, the implications of his sensory challenges will begin to attract new attention. Hamilton notes, “I totally empathize with Beethoven’s struggles, as I’ve had some of them myself. The more we understand about a composer’s emotional world, means a deeper knowledge of their music. People will be inspired with Beethoven’s decision to continue to compose, even after what he could actually hear was only in his own mind. I personally am inspired by his ability to rise above his disability. I wish that more of my musician colleagues, and the world in general, would get past the stigma of hearing loss.”

Neuman, being himself profoundly hard of hearing, identifies thoroughly with those issues. As for Trevathan, her career on the stage is no less dependent upon hearing than is a musical career. Recalling the play’s development process, she observes, “Our team spoke quite a bit, especially in early meetings developing the script, about how … loss of anything you’ve come to rely on, really comes with an encoded opportunity for tremendous growth. I think of Monet’s cataracts resulting in a shift toward abstraction in his later paintings.” With Incessant Hum, one can explore Beethoven’s situation, both its limitations and its freedoms.

Three Denver-area performances of Jeff Neuman’s Incessant Hum are scheduled, all with actors Chelsea Frye and Chris Kendall, director Mare Trevathan, and musicians Andrew Cooperstock (piano), Paul Primus and John Fadial (violins), Barbara Hamilton (viola), and Beth Vanderbourg (cello):

- January 14 at 730pm at Broomfield Auditorium, 3 Community Park Road (west of Bldr Trnpike at 287 & 128 near First Bank Center), Brown Paper Tickets

- January 18 at 6pm at Opus Two Hall, 9167 Davidson Way in Lafayette, Gala and performance (off of Baseline near 95th Street – reservations required) Brown Paper Tickets for Gala

- January 19 at 2pm at the Boulder Public Library, 1001 Arapahoe Avenue, Boulder (Canyon Theatre)

Tickets are available through the Colorado Chamber Players’ website.

Further information about the playwright’s productions, plays, and other writing can be found at: www.theaterbyjeff.com.